Volume 1 - Issue 3

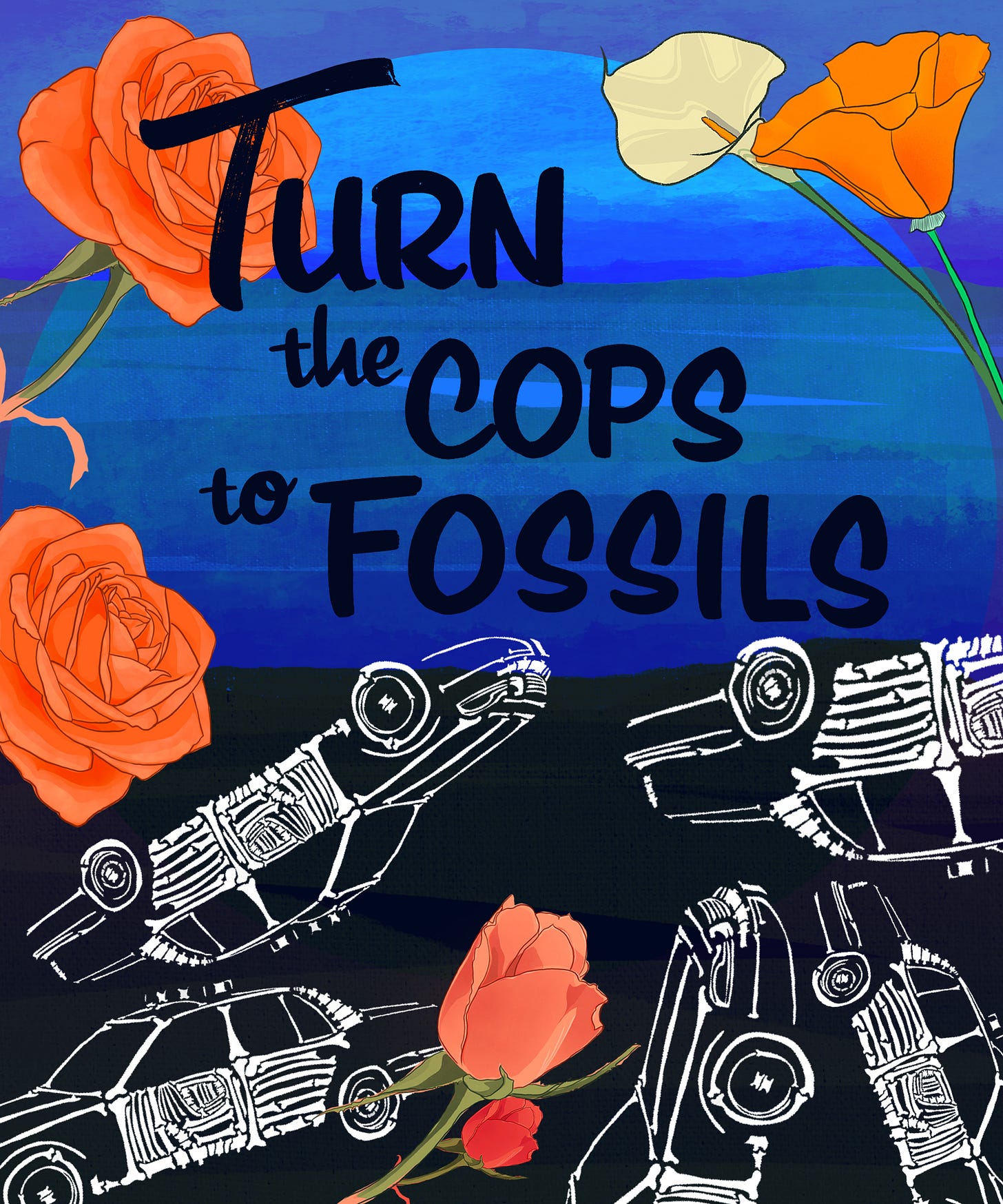

Art by Kate DeCiccio

2015

In July 2019, I ran away from Chicago. I had become a person I didn’t quite understand or know when I was there. I spent a lot of 2019 living abroad, and I realized that I was more myself there than in Chicago. I didn’t understand why, until recently—in Chicago, I wasn’t just “Tess” but rather I was “Tess, the teacher” or “Tess, the organizer.” I am not special, but the way Black liberation work had at least been established in Chicago was so intense, you become the work. You become the figure.

In 2015, I moved to my hometown, Chicago, after following and being inspired by the abolitionist work of organizations like We Charge Genocide from afar. I had been doing anti-police activism and journalism in NYC and thought about how much I could learn in Chicago.

I did not know how to access organizations immediately, and many felt exclusive, but Aislinn Sol, an incredible socialist organizer and lovely human, invited me to BLM Chicago events and protests at police board hearings that July. She invited me to come with her and others on a bus to Cleveland for the first Movement For Black Lives gathering. I do not remember any of the workshops. I do remember the moment we were preparing to board the bus to return. I passed a 14 year old boy being arrested by the police for underage drinking. I went to where the bus was boarding, and told Jasson Perez, a BYP 100 organizer at the time, what was happening. He, along with many others, began de-arresting the boy. I called the boy’s mother and tried my best to tell her where he was located in a city I did not know, as a police officer maced the all-Black crowd of organizers and activists. We eventually de-arrested the boy and made the journey back to Chicago. That experience was intense, traumatizing, but for a glimpse, we felt powerful against the State. It was emblematic of what my experiences would be in the years to come.

I joined Assata’s Daughters (AD) in September 2015 and developed its youth program for young Black girls and helped develop our own political education. We planned and carried out direct actions along with BYP 100, BLM Chi, FLY, OCAD and alongside other freedom fighters demanding that Chicago “defund the police, and fund Black futures.” I studied the work of the Black Panther Party and Combahee River Collective, and I tried to help build Assata’s Daughters into an organization that honored the legacies of those groups. These organizations spoke specifically about multiracial anti-capitalist organizing, and yet sometimes we misinterpreted their work to be Black Nationalist.

We helped organize a complicated direct action blocking multiple intersections of the International Association of the Chiefs of Police Convention, “the largest and most important law enforcement event of the year,” with over 15,000 attendees from 83 different countries. For weeks, we built, prepped, and rehearsed safely locking into place. On a chilly October morning, we left our phones behind, bundled up, and, wearing shoes without laces (so they would not be confiscated in jail), strapped ourselves with carabiners to an elaborate PVC-pipe contraption in front of McCormick Place.

Police chiefs were blocked for hours until SWAT teams cut us apart and arrested us. It was my first political arrest. I’ll never forget the moment I was released and walked out to the lobby full of people, who had also been arrested, clapping and surrounded by food. It didn’t feel heroic or normal. It felt odd. I found and sat on the precinct floor, next to the one person who seemed to share my apathy or confusion, and we waited until everyone else was released. I think disruption is important, and I loved that the action was multiracial, but I didn’t feel that we had shifted power away from the State nor did I feel that there were next steps or ways to escalate. We were bailed out quickly because of the work of grassroots fundraising from the Chicago Bond Fund.

Assata’s Daughters work was uplifting and the youth work was the best work I’ve ever been a part of. Every Wednesday night, I was facilitating programming about freedom struggles, the history of incarceration, the Pullman Porters, the Black Panther Party, through music, art, movement and literature to Black girls aged 5-14. We farmed and grew our own food right in our community, and we went on trips to meet other organizers throughout the City. A group of our young members lost their father and uncle to police violence, and the program met the world to them. We applied for and received grants, but I also spent money out of pocket on seeds and garden supplies as did our other members. None of us were paid, and instead we took on volunteer roles on teams such as “Grants and Fundraising,” “Food and Logistics,” “Facilitating.” We provided meals weekly for our girls and tried to support Black owned businesses when we ordered the meals. We relied on the support of our co-strugglers who donated their time and resources to us too. It was beautiful what we were able to build without non-profit status or institutional wealth. But these beautiful moments were shadowed by dark moments on a regular basis.

In November, after a horrific coverup, the city released the footage of Laquan McDonald, a 17 year old Black boy, shot 16 times by CPD officer Jason Van Dyke. We took to the streets that night and some organizers spoke about “righteous rage” and “creating space for Black people to express their rage,” which meant we clashed with the police. They violently brutalized and arrested a Black organizer. We had to immediately pivot to organizing jail and court support for the arrested organizer. These tense moments happened frequently because we fought fiercely for a world that was safe, loving and fruitful for Black people.

In AD, when we were not working with kids, we coordinated elaborate campaigns, using banner drops and disruptions, to oust the states attorney, Anita Alvarez. When we met in person, we removed technology from the room to prevent surveillance, and used coded language to communicate via WhatsApp and Signal. Again, we did not have much money but used our limited funds to pay for banner supplies and food. None of us were or are rich, but instead believed in the work we were doing for our under resourced communities.

We helped shut down a Trump Rally, to connect Trump’s message to the messaging of Anita Alvarez. This was the only rally Trump had to cancel on his campaign trail, which felt like a win until fighting broke out between Trump supporters and Bernie supporters, and we were stuck in the mix. We watched as another comrade was brutalized by the police, and while some organizers left for an already scheduled retreat, several of us spent the night searching for him—first at a hospital, which we were physically removed from, and then jail. The morning after, I was interviewed by MSNBC, which I didn’t want to do because I didn’t understand the value of interacting with Mainstream Media. I was criticized for doing the interview because people felt that people who were “leaders” should have been the spokespeople. My work was rooted in a love of my community yet I was still scrutinized.

On election day, as people voted, we flew a banner across Chicago “#ByeAnita.” We won that campaign and Alvarez lost. We were tired, from our sleepless nights, and our full time jobs, but we began to imagine the next campaign, saving Chicago State University, which we failed to adequately support. We tried to get a killer cop Dante Servin, who murdered Rekia Boyd in 2012, fired from the CPD. We wanted to show that the city spent more salaries for killer cops than on a public university that predominantly supported Black students. We organized more direct actions and took more arrests.

We worked, we dreamed, we fought, we sometimes won and felt good, but the State always worked to crush us. We kept dreaming.

On one occasion, we held a noise demonstration on the sidewalk in front of the home of Dante Servin, facing Douglass Park, in a predominantly Black neighborhood. He came out and pointed what appeared to be an AK-47 at us and said he’d kill us too if we didn’t leave. Afterwards we just ate chicken. The horrifying became almost mundane. Servin resigned before he could be fired and received a pension.

In February 2017, a month after Trump’s inauguration, one of AD’s members, and one of the most thoughtful and compassionate humans I have ever known, 11-year-old Takiya Holmes, was killed by a stray bullet in a parked car. She was sitting with her 3 year old brother in her mother’s car and on a block known as “Chicago’s most violent block.” We were supposed to fear that block, but I taught on that block, and I loved it. I love so many people on it still, and I realized loving a block was inadequate. We spent every day with Takiya’s family at the hospital, provided food, water, collected funds for what would become funeral costs. We coordinated flower deliveries, more food deliveries, and found ways of memorializing beautiful Takiya in our community garden. We held space for grief with our other little ones, and we began to think more deeply about the role of community violence. We supported efforts to distribute food and hygiene products in that community, and the organization restructured. I left the organization shortly after this. As much as we pushed to change, it always felt like we were pushed back with double the force.

Community violence is a symptom of poverty and racism. My community, with its high rates of gun violence, had very few resources. Had very few options. My own block, also violent, felt bleak and gray. At that point, I understood that our organizing was not as connected to poor communities as we had initially thought it was. When considering the obstacles of Black people’s liberation, we decided to focus on police violence because the State, instead of addressing the lack of resources in our communities, chose to respond with police violence. But, I also think we had a limited analysis around class. A lack of resources is what creates unsafe neighborhoods, and somehow I think a lot of our organizing failed to address this.

I felt strange, and unwhole after leaving the Chicago organizing world, even as I remained in Chicago. The traumas I experienced organizing and that I heard about from my students, as I supported them—emotionally, financially, professionally—added up, too, until I couldn’t deal with it anymore, and I ran away.

Chicago organizing demands were always rooted in an abolitionist politic, but I believe that they lacked a clear anti-capitalist analysis. We were most successful when we worked in multiracial, working class coalitions and in organizations that centered poor and working class Black people.

This year, I stepped back into organizing, back in New York, and I committed a lot of my time to organizing for the Bernie Sanders campaign. I phonebanked across the country and canvassed in places like very white New Hampshire and learned that there were commonalities between my struggle and the struggles of all working class people. I finally understood that our work has to be anti-capitalist and inclusive of all struggles. We need to be willing to fight for somebody we don’t know.

I wouldn’t have learned those lessons, without my Chicago lessons, and I hope that as we move forward in this most recent iteration of Black struggle, that we connect our struggle to other struggles. There are very few winners in capitalism, and we cannot defeat racism without also destroying capitalism. I’m interested in building coalitions of co-strugglers who, regardless of race and experience, are completely invested in anti-racist work that seeks to tear down capitalism. I felt that #NotMeUs provided a container for that work, and I’m hopeful that we can get there again. One of my Chicago heroes, the revolutionary Black Panther Party socialist, Fred Hampton said, “We're gonna fight racism with solidarity,” and we will.

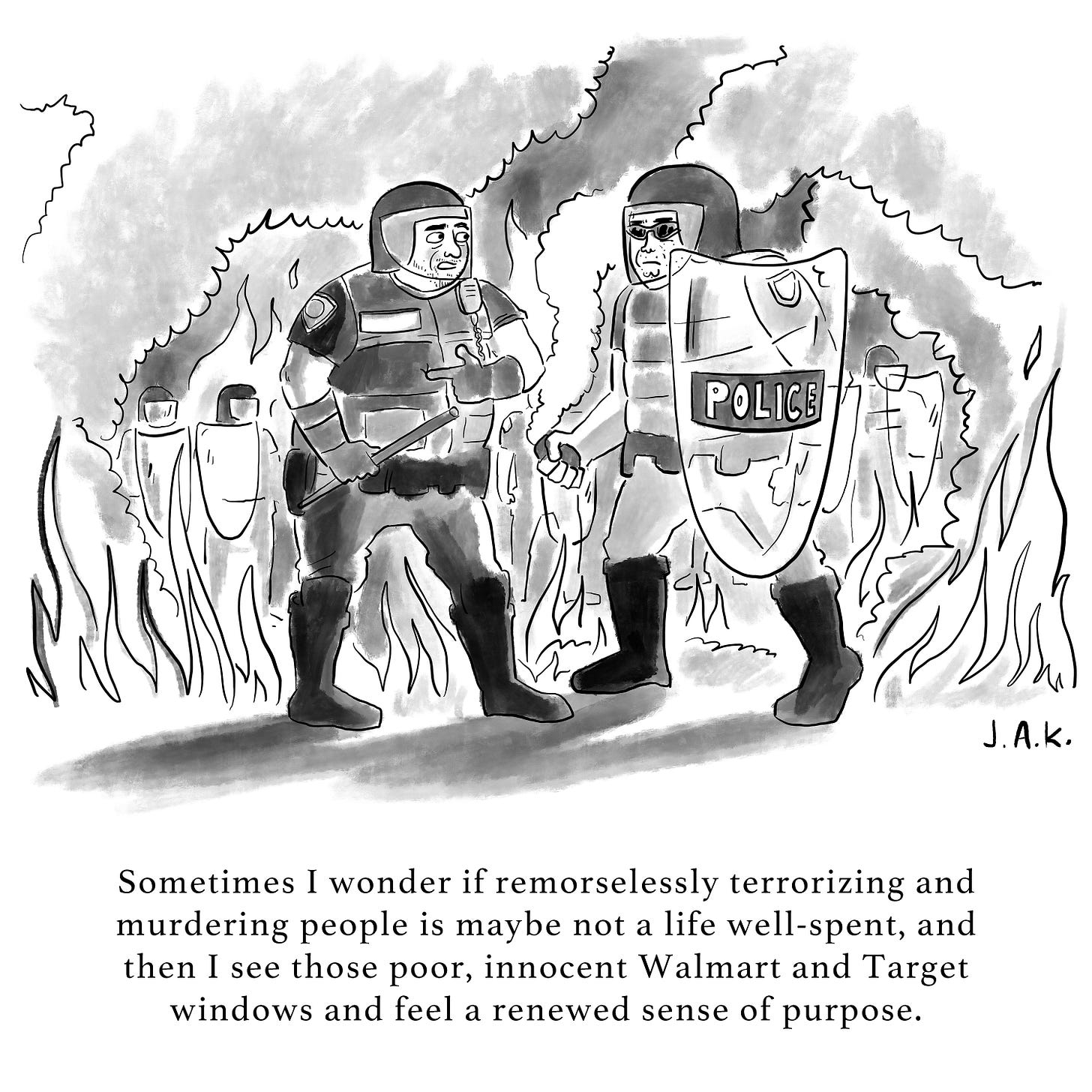

Cartoon by Jason Adam Katzenstein

fred hampton at lake michigan

Cartoon by Jason Adam Katzenstein